by Gary Lord

Home - Genesis - 2007 - 2008 - 2009 - Early 2010 - Mid 2010 - Late 2010 - End 2010 - Early 2011 - Mid 2011 - Late 2011 - End 2011 - Early 2012 - Late 2012 - Early 2013- Late 2013 - 2014 - 2015 - Early 2016 - Late 2016 - 2017-19

Chapter Nine: Early 2011

Early 2011 saw the US government stepping up multiple attacks on WikiLeaks, despite continuing widespread public support for the brave whistle-blowing publishers. Meanwhile, former media partners were quickly turning into hostile critics.

At this stage, many observers (including myself) were beginning to wonder if Julian Assange might have Aspergers Syndrome. He brushed away such suggestions as unimportant but was later diagnosed with the condition. People with Aspergers Syndrome are on the high-functioning end of the Autism Spectrum and often extremely intelligent. They are sometimes accused of lacking empathy when in fact they may just be lacking certain social skills, and they can often become obsessed with certain topics. Giveaway symptoms for Assange included his long, rambling, monotone speeches, his fearless approach to public criticism, and his frequent capacity to infuriate people around him with his single-minded determination.

Bank of America

On 30 November 2010, a day after the Cablegate release, shares in Bank of America dived by 3 percent as rumours spread that it would be the target of WikiLeaks' next big release.

On Monday, Julian Assange, founder of the WikiLeaks, said his group plans to release tens of thousands of internal documents from a major U.S. bank early next year, according to an interview posted online by Forbes Magazine.

Interviewed in Malaysia a year earlier, Assange had told IDG News Service:

"At the moment, for example, we are sitting on 5GB from Bank of America, one of the executive’s hard drives… Now how do we present that? It’s a difficult problem. We could just dump it all into one giant Zip file, but we know for a fact that has limited impact. To have impact, it needs to be easy for people to dive in and search it and get something out of it."

In the same interview, Assange revealed how WikiLeaks had learned from lack of media coverage in previous leaks:

"It’s counterintuitive," he said. "You’d think the bigger and more important the document is, the more likely it will be reported on but that’s absolutely not true. It’s about supply and demand. Zero supply equals high demand, it has value. As soon as we release the material, the supply goes to infinity, so the perceived value goes to zero."

He said WikiLeaks wanted to "get as much substantive information as possible into the historical record, keep it accessible, and provide incentives for people to turn it into something that will achieve political reform."

The Cablegate release had done just that. But now, with a green light from Senator Joe Lieberman (see previous chapter), Bank of America executives were keen to take proactive action against WikiLeaks. They did not know that - thanks to "disgruntled former employees" - WikiLeaks was no longer even in possession of their hard drive data.

*

Virginia-based law firm Hunton & Williams (H&W) had an unprofitable data intelligence project called Team Themis, which was close to being folded in early December 2010 when suddenly they got an "urgent request" from "a major US bank" that was "seeking help against WikiLeaks".

"I need a favor. I need five to six slides on Wikileaks — who they are, how they operate and how this group may help this bank. Please advise if you can help get me something ASAP. My call is at noon"

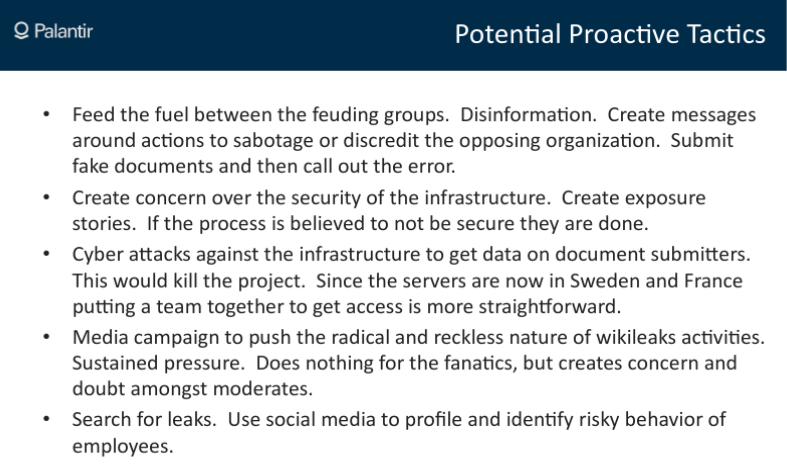

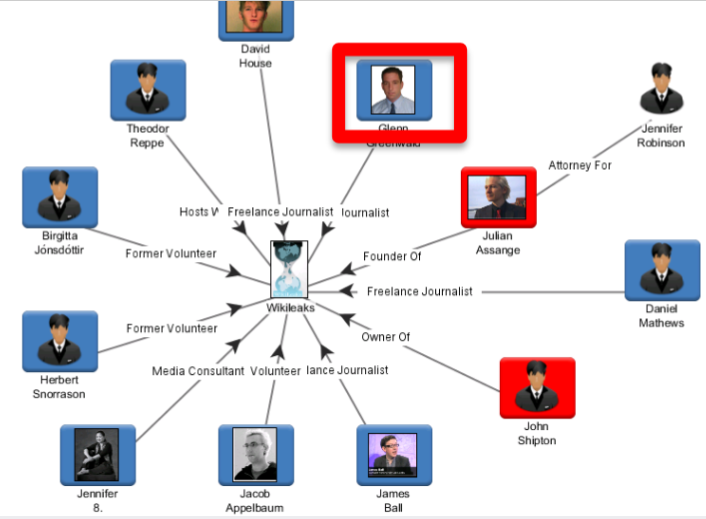

Team Themis included staff from Palantir Technologies, Berico Technologies, and HBGary Federal, whose CEO Aaron Barr rushed out a PowerPoint presentation that called for "disinformation", "cyber attacks" and a "media campaign" against WikiLeaks.

A former Navy Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) officer, Aaron Barr insisted that US civil rights lawyer and journalist Glenn Greenwald was a critical target:

"It is this level of support we need to attack. These are established professionals that have a liberal bent, but ultimately most of them if pushed will choose professional preservation over cause, such is the mentality of most business professionals. Without the support of people like Glenn WikiLeaks would fold."

In January 2011 a New York Times article confirmed that the Bank of America’s "counterespionage work" against WikiLeaks entailed constant briefings for top executives and the hiring of "several top law firms".

But in Febraury 2011 Aaron Barr went a step too far, boasting to the Financial Times that his firm HB Gary Federal was about to expose #Anonymous hackers. In retaliation, #Anonymous hacked into HB Gary’s email accounts and published 50,000 of their emails online. They also hacked Barr’s Twitter and other online accounts. Thus the secret Powerpoint slides of "Team Themis" (above) were publicly exposed. The emails also suggested that Team Themis had been set up at the request of the Chamber of Commerce to infiltrate ThinkProgress and other pro-Union groups.

As Glenn Greenwald noted, based on the poor quality of their research and seemingly illegal proposals, Team Themis at first looked like "just some self-promoting, fly-by-night entities of little significance". But "the firms involved here are large, legitimate and serious, and do substantial amounts of work for both the U.S. Government and the nation’s largest private corporations". HBGary claimed to have a cache of "zero-day exploits" - cyber attacks for which there is no existing remedy - and expertise in "computer network attack", "custom malware development" and "persistent software implants."

And perhaps most disturbing of all, Hunton & Williams was recommended to Bank of America’s General Counsel by the Justice Department — meaning the U.S. Government is aiding Bank of America in its defense against/attacks on WikiLeaks.

Greenwald said the episode highlighted "just how lawless and unrestrained is the unified axis of government and corporate power".

The firms the Bank has hired (such as Booz Allen) are suffused with the highest level former defense and intelligence officials, while these other outside firms (including Hunton & Williams and Palantir) are extremely well-connected to the U.S. Government. The U.S. Government’s obsession with destroying WikiLeaks has been well-documented. And because the U.S. Government is free to break the law without any constraints, oversight or accountability, so, too, are its "private partners" able to act lawlessly…

It’s impossible to imagine the DOJ ever, ever prosecuting a huge entity like Bank of America for doing something like waging war against WikiLeaks and its supporters. These massive corporations and the firms that serve them have no fear of law or government because they control each.

Bank of America issued a "carefully worded statement". H & W refused to comment. Palantir publicly apologized "to progressive organizations in general, and Mr. Greenwald in particular, for any involvement that we may have had in these matters". HBGary distanced themselves from Aaron Barr, who resigned, and HBGary Federal was folded.

- NOTE

-

WikiLeaks supporters were still hoping to see the release of a Bank of America executive’s hard drive; the loss of this data was only confirmed months later when negotiations with Domscheit-Berg broke down and the leaked data was destroyed.

*

Twitter "Subpoenas"

While financial groups sought to cut off support for WikiLeaks, the US Department of Justice was still pursuing their own avenues of attack.

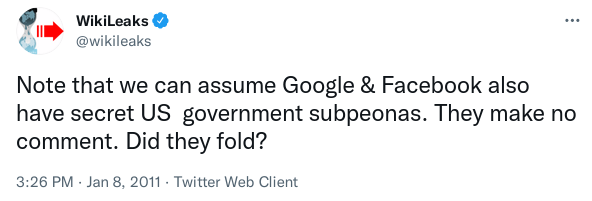

On 8 January 2011, Twitter revealed that the US Department of Justice had issued them with a court order, dated 14 December 2010 (PDF), for "all records" and "correspondence" relating to accounts "registered to or associated with WikiLeaks". Julian Assange and Bradley Manning were specifically named, along with Iceland MP Birgitta Jónsdóttir, Tor developer Jacob Appelbaum, and Dutch hacker Rop Gonggrijp, who had helped work on the Collateral Murder video.

Twitter advised affected users that they had ten days to oppose the request for information about their accounts.

"I think I am being given a message, almost like someone breathing in a phone," tweeted Jónsdóttir. "USA government wants to know about all my tweets and more since November 1st 2009. Do they realize I am a member of parliament in Iceland?"

Glenn Greenwald was shocked by the broad scope of the information sought by the Justice Department.

It includes all mailing addresses and billing information known for the user, all connection records and session times, all IP addresses used to access Twitter, all known email accounts, as well as the "means and source of payment," including banking records and credit cards. It seeks all of that information for the period beginning November 1, 2009, through the present.

The New York Times reported that this was "the first public evidence" of Attorney General Eric Holder’s criminal investigation, which they expected would be "fraught with legal and political difficulties". Gonggrijp noted that the affected users only found out about the order "because Twitter did the right thing and successfully fought for a second court order so they were able to tell us". Citing concerns for his young family, Gonggrijp later terminated his public support for WikiLeaks.

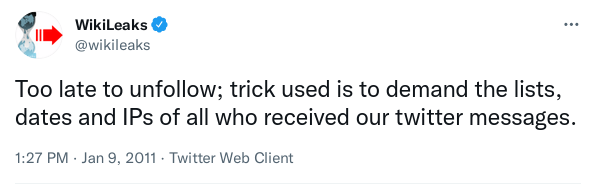

The DoJ court order, which was widely misreported as a "subpoena", caused outrage on Twitter, with WikiLeaks warning that 637,000 followers were now being targeted by the US government "under section 2.B" of the order (user names and "destination IP addresses" of anyone receiving communications from the named individuals). Enraged followers threatened a class action lawsuit against the US government. Others were intimidated into unfollowing @wikileaks, but within a week the account had a net gain of 12,000 followers (hello again Streisand Effect).

Iceland’s Foreign Minister Oessur Skarphedinsson told German media it was not acceptable that US authorities had demanded such information. Iceland’s Interior Minister described the Justice Department’s efforts as "grave and odd":

"If we manage to make government transparent and give all of us some insight into what is happening in countries involved in warfare it can only be for the good."

In March 2011 a judge in the Eastern District of Virginia court upheld the Department of Justice’s demand for Twitter data, despite complaints by Appelbaum, Gonggrijp and Jonsdottir that it violated constitutional protections for free speech. Twitter Guidelines now state that private information about Twitter users will be released in response to "appropriate legal process such as a subpoena, court order [or] other valid legal process".

*

After some deliberation, Jacob Applebaum decided to push ahead with his planned return to the USA on 10 January, but organised for representatives from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to meet him at the airport. He then posted a long series of tweets about the constant harrassment he received when traveling through US airports.

The CBP agents in Seattle were nicer than ones in Newark. None of them implied I would be raped in prison for the rest of my life this time.

*

Early media attacks

On 31 December 2010 Alternet published a list of eight "Smears and Misconceptions" that were already being regularly pushed by media organisations:

-

Fearmongering that WikiLeaks revelations will result in deaths.

-

Spreading the lie that WikiLeaks posted all the cables.

-

Falsely claiming that Assange has committed a crime regarding WikiLeaks.

-

Denying that WikiLeaks is a journalistic enterprise.

-

Denying a link between Ellsberg’s Pentagon Papers and WikiLeaks, despite Ellsberg’s support of the site.

-

Accusing Assange of profiting from WikiLeaks.

-

Calling Assange a terrorist.

-

Minimizing the significance of the cables.

There were also easily dismissed claims that WikiLeaks had acquired their files by hacking. Sadly, even WikiLeaks' trusted media partners were guilty of indulging these deliberate smears and outright lies, with British newspaper the Guardian quickly becoming the most hostile organisation.

The very idea of media partnerships had first been conceived when Julian Assange met with Guardian journalist Nick Davies in a Brussels cafe. But on 17 December 2010, Davies published an article titled Ten Days In Sweden, which provided lurid details of the Swedish sex allegations directly from the Swedish police file on the Assange case. Davies said the file, which would normally have remained secret to protect the privacy of all parties concerned, just "happened to make its way quite legitimately into the hands of somebody I have come across in the past". He refused to identify his source, who almost certainly committed a crime by leaking the file.

Guy Rundle later read the full police report in Swedish and claimed "Davies has fundamentally distorted the record" with key details omitted and "distortingly oversimplified translation".

And of all Nick Davies’ omissions, perhaps the most significant was that of the final witness, who was questioned about text messages she exchanged with Sofia Wilén discussing seeking revenge on Assange, and getting money from newspapers (“it was just a joke”).

In the first week of January 2011, Bianca Jagger (who had helped pay Julian Assange’s bail) published a rebuttal of Nick Davies' rebuttal of her rebuttal of his original "Ten Days In Sweden" article. Davies, who acknowledged having fallen out with Assange months earlier, had rejected Jagger’s claims that his one-sided article, peppered with lurid sexual details, amounted to "trial by newspapers".

Jagger dismissed Davies' ludicrous claim that he was defending his source just like WikiLeaks defended theirs, noting "there is a profound difference between exposing the deeds of powerful governments, corporations and the rich and throwing mud at those who released the information". She also made an important point which would have profound repercussions for years to come:

Assange cannot defend himself at this point; all he can do is refute these allegations in the broadest terms. Davies knows that Assange’s lawyers will insist that he does not publicly engage in a rebuttal of the details in these allegations himself, when he is facing extradition and possible criminal charges. He is thoroughly disadvantaged by what Davies has done.

Davies eventually washed his hands of any responsibility for the article that bore his name:

The reality is that I didn’t write the story which the Guardian published. The copy which I filed was completely re-written in the Guardian office, a commonplace event in a newsroom.

But the Guardian’s animosity to Assange continued. On 3 January 2011 the Guardian published an article that accused WikiLeaks of endangering the life of Morgan Tsvangirai, the leader of the democratic opposition in Zimbabwe, by publishing a cable about him. The author James Richardson, a US Republican working for a "social media public affairs agency" (not disclosed to readers), argued that "WikiLeaks may have committed its own collateral murder."

"WikiLeaks ought to leave international relations to those who understand it – at least to those who understand the value of a life."

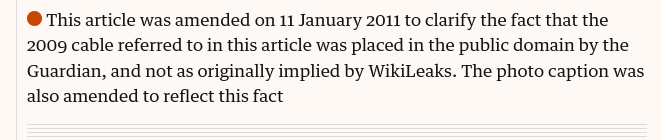

There was a major problem with this claim: it was the Guardian themselves who had selected the cable from the archive and chosen to publish it in early December. Nevertheless, the false claim was repeated in the Wall Street Journal, the Atlantic, Politico and other sites. It took over a week for the Guardian to publish a footnote:

But as Glenn Greenwald noted, the article - which should have been deleted - was not fundamentally altered. The misleading headline remained, along with repeated false claims blaming WikiLeaks for publishing the cable.

This is the propaganda campaign - created by the U.S. Government and (as always) bolstered by the American media - which is being used to justify WikiLeaks' destruction (and, with it, the repression of some of the most promising avenues for transparency and investigative journalism we’ve seen in many years)… WikiLeaks didn’t steal anything. They didn’t break any laws. They did what newspapers do every day, what investigative journalism does at its core: expose secret, corrupt actions of those in power. And the attempt to criminalize WikiLeaks is thus nothing less than a full frontal assault on press and Internet freedoms.

Guardian deputy editor Ian Katz belatedly explained that Richardson was "a first-time contributor to our comment website" and neither he nor the US-based editor who posted the article were aware of the "somewhat complicated process" used to publish the cables (never mind the process had been widely reported weeks earlier). Katz said the article was posted on a bank holiday after Christmas when the Guardian’s WikiLeaks editing team was not around. But the misleading article is still online, more than ten years later. As is the Wall Street Journal’s uncorrected version.

*

More Death Threats

On 11 January 2011 Julian Assange’s routine case management hearing at Belmarsh Magistrates Court was swamped with media and supporters. The Guardian’s live-blog of the event included continuing global fallout from the US cable publications and highlights from a 35-page skeleton outline of court arguments from Assange’s lawyers.

There were valid security concerns around Assange’s court appearance, especially following a recent mass shooting in Arizona where a US politician was shot. WikiLeaks published a statement condemning violent threats:

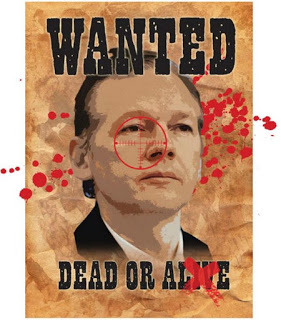

WikiLeaks staff and contributors have also been the target of unprecedented violent rhetoric by US prominent media personalities, including Sarah Palin, who urged the US administration to “Hunt down the WikiLeaks chief like the Taliban”. Prominent US politician Mike Huckabee called for the execution of WikiLeaks spokesman Julian Assange on his Fox News program last November, and Fox News commentator Bob Beckel, referring to Assange, publicly called for people to "illegally shoot the son of a bitch." US radio personality Rush Limbaugh has called for pressure to "Give [Fox News President Roger] Ailes the order and [then] there is no Assange, I’ll guarantee you, and there will be no fingerprints on it.", while the Washington Times columnist Jeffery T. Kuhner titled his column “Assassinate Assange” captioned with a picture Julian Assange overlayed with a gun site, blood spatters, and “WANTED DEAD or ALIVE” with the alive crossed out.

John Hawkins of Townhall.com has stated "If Julian Assange is shot in the head tomorrow or if his car is blown up when he turns the key, what message do you think that would send about releasing sensitive American data?"

Christian Whiton in a Fox News opinion piece called for violence against WikiLeaks publishers and editors, saying the US should "designate WikiLeaks and its officers as enemy combatants, paving the way for non-judicial actions against them."

WikiLeaks spokesman Julian Assange said: "No organisation anywhere in the world is a more devoted advocate of free speech than Wikileaks but when senior politicians and attention seeking media commentators call for specific individuals or groups of people to be killed they should be charged with incitement — to murder. Those who call for an act of murder deserve as significant share of the guilt as those raising a gun to pull the trigger."

A website addresss, JulianAssangeMustDie.com, was traced to a rightwing US blogger (and deleted soon afterwards).

Meanwhile the economic threats from US officials continued to escalate. On 12 January 2011 WikiLeaks responded to Rep. Peter T. King’s calls for a US embargo of WikiLeaks.

WikiLeaks today condemned calls from the chair of the House Committee on Homeland Security to "strangle the viability" of WikiLeaks by placing the publisher and its editor-in-chief, Julian Assange, on a US "enemies list" normally reserved for terrorists and dictators.

King specifically wanted to target Knopf, a New York publisher who had recently agreed to pay Assange for an autobiography. Assange said the book royalties would "keep Wikileaks afloat". An article in the Atlantic ridiculed the madness of such a McCarthyist blacklist: "you could conceivably break the law merely by buying his book, or contributing to a WikiLeaks defense fund".

WikiLeaks was under massive pressure but clearly not going down without a fight. In a 12 January interview with John Pilger, Assange again mentioned the existence of "insurance files":

"WikiLeaks is now mirrored on more than 2,000 websites… If something happens to me or to WikiLeaks, ‘insurance’ files will be released…. There are 504 US embassy cables on one broadcasting organisation and there are cables on Murdoch and News Corp.”

Was it a bluff? In years to come, WikiLeaks would repeatedly post such encrypted "insurance files" online. This lead to a lot of wild speculation about the contents, and much of that speculation eventually solidified into misguided belief. Uninformed critics still angrily disclaim how WikiLeaks "promised" to post something but never did.

*

On 8 January 2011 WikiLeaks launched a new defense fund for Julian Assange, tweeting: "let us see Paypal try to close this one down too!" The following week saw more global protests. A rally in Sydney, Australia drew around a thousand supporters. This followed another huge Sydney protest on 14 December 2010, with another one planned for 6 February 2011. WikiLeaks supporters around the world were energised, outraged, and working together to support their heroes.

In February 2011 Snorre Valen, a member of the Norwegian parliament, nominated WikiLeaks for the Nobel Peace Prize. The Sydney Peace Foundation also announced that it would award a rare gold medal to WikiLeaks publisher Julian Assange for his "exceptional courage and initiative in pursuit of human rights". The Peace Medal, distinct from the foundation’s annual Peace Prize, was previously only awarded to the Dalai Lama, Nelson Mandela, and Buddhist leader Daisaku Ikeda.

"Assange has championed people’s right to know and has challenged the centuries-old tradition that governments are entitled to keep the public in a state of ignorance."

On 2 March 2011 a meeting was organised at Parliament House in Canberra, where Assange lawyers and prominent supporters addressed a group of Australian politicians and their staff. Those in attendance included future Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, a former lawyer and Chair of the Australian Republican Movement, who had successfully defended a former MI5 official’s publication of the tell-all book Spycatcher. Turnbull occasionally used the Assange case to score points against the ruling Rudd-Gillard Labour government, but he never challenged US treatment of WikiLeaks' Australian founder.

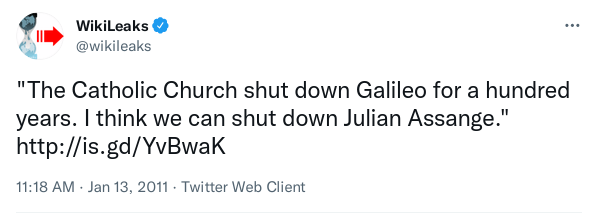

Meanwhile another senior Australian Liberal Party politician anonymously boasted that Julian Assange would be treated the same way as Galileo, who was found guilty of heresy and spent his life under house arrest for proving that the earth revolves around the sun.

Manning Quantico Torture Protests

Public protests for Assange and WikiLeaks always featured prominent support for Chelsea (then still "Bradley") Manning, who had now been jailed under turturous conditions at the Quantico brig for over five months. On 24 January, two Manning supporters (including regular visitor David House) were turned away from the facility after they attempted to deliver a petition of support with 42,000 signatures. On the following day, NBC reported that US military officials had placed Manning on suicide watch.

The official said that after Manning had allegedly failed to follow orders from his Marine guards, [Brig Commander James] Averhart declared Manning a "suicide risk." Manning was then placed on suicide watch, which meant he was confined to his cell, stripped of most of his clothing and deprived of his reading glasses — anything that Manning could use to harm himself.

Manning later claimed that the guards had created a scene by issuing conflicting demands such as "turn left, don’t turn left". An investigation found that the Brig Commander had acted unlawfully, and he was replaced.

Manning was removed from suicide watch on January 21 but remained on POI (Prevention Of Injury) status, despite repeated calls from Army health professionals for this to be lifted. Manning’s lawyers filed a complaint explaining exactly what this status entailed:

Like suicide risk, he is held in solitary confinement. For 23 hours per day, he will sit in his cell. The guards will check on him every five minutes by asking him if he is okay. PFC Manning will be required to respond in some affirmative manner. At night, if the guards cannot see him clearly, because he has a blanket over his head or is curled up towards the wall, they will wake him in order to ensure that he is okay. He will receive each of his meals in his cell. He will not be allowed to have a pillow or sheets. He will not be allowed to have any personal items in his cell. He will only be allowed to have one book or one magazine at any given time to read. The book or magazine will be taken away from him at the end of the day before he goes to sleep. He will be prevented from exercising in his cell. If he attempts to do push-ups, sit-ups, or any other form of exercise he will be forced to stop. He will receive one hour of exercise outside of his cell daily. The guards will take him to an empty room and allow him to walk. He will usually just walk in figure eights around the room until his hour is complete. When he goes to sleep, he will be required to strip down to his underwear and surrender his clothing to the guards.

On 24 January 2011, after blocking payments from Manning supporters for nearly a month, PayPal finally backed down and reinstated the account of Courage to Resist, a partner of the Bradley Manning Support Network. This followed a press release and a petition with over 10,000 signatures.

On the same day. Amnesty International issued a call for the USA to "alleviate the harsh pre-trial detention conditions of Bradley Manning." They ignored pleas to show similar support for Julian Assange.

We are unaware of any legal action having yet been taken against Julian Assange for releasing the documents. As such, Amnesty International is not in a position to comment on any possible case against him specifically, as there are no charges to comment on.

Amnesty also refused to comment on the Swedish allegations, arguing only that "due process should be followed". Their strange lack of interest in the Assange case was to endure many years, with only very occasional and limited mentions.

On Sunday 13 March, P. J. Crowley, a spokesman for the Department of State, was forced to resign after he criticized Manning’s inhumane treatment as "ridiculous and counterproductive and stupid." When President Obama was asked whether he agreed with Crowley, he said Pentagon officials had assured him that the conditions of Manning’s 10 months in pretrial solitary confinement were "appropriate and are meeting our basic standards".

A few days later, Britain’s foreign secretary William Hague was asked about Manning’s alleged torture by Welsh MP Ann Clwyd, who compared it to the treatment of prisoners at Guantanamo Bay. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) also issued a press release condeming the "cruel and unusual" treatment of Manning, whose status as a UK citizen was confirmed weeks later.

An "International Bradley Manning Support Day" was held on 20 March, with global protests in support of the alleged whistleblower. 80 year old Pentagon Papers whistle-blower Daniel Ellsberg was arrested twice in two days after refusing to move from protests outside the Quantico base.

*

Stratfor

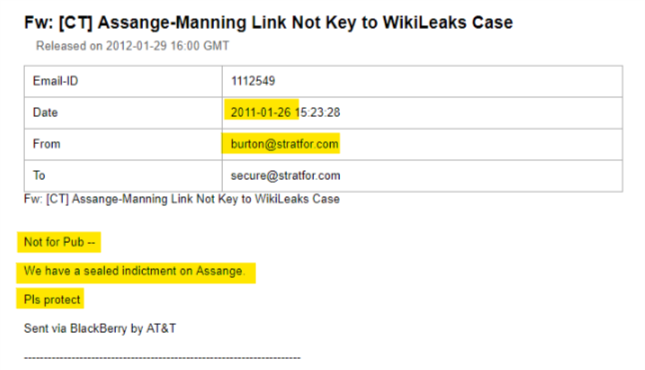

Stratfor is a Texas-based security information business that relies on close communication with US intelligence agencies. Many Stratfor staff are former CIA agents. In early 2011, Stratfor’s Vice-President for Counterterrorism and Corporate Security was Fred Burton, a former Deputy Chief of the Department of State’s counterterrorism division for the Diplomatic Security Service.

On 26 January 2011, Burton sent an email to Stratfor staff revealing that the US government now had "a sealed indictment on Assange". He asked staff to protect this information and not publish it.

Burton’s email remained secret until February 2012, when Stratfor was hacked by #Anonymous and WikiLeaks published the files.

Burton’s hacked emails also stated: "Assange is going to make a nice bride in prison. Screw the terrorist. He’ll be eating cat food forever." Like Palantir and HBGary’s Aaron Barr, he recommended destroying WikiLeaks' financial base and infrastructure using "the same tools used to dismantle and track" terrorists.

"Find out what other disgruntled rogues inside the tent or outside [sic]. Pile on. Move him from country to country to face various charges for the next 25 years. But, seize everything he and his family own, to include every person linked to Wiki."

Despite this further evidence of a US indictment, media commentators and senior government officials in Britain, Australia, and Sweden - many of whom must also have known about the sealed indictment - continued to pretend that Assange’s fears of extradition to the USA were entirely baseless.

In August 2012, Reuters falsely reported that the USA had "no current case" against Assange and State Department spokeswoman Victoria Nuland dismissed his extradition concerns as "wild assertions".

“He is clearly trying to deflect attention away from the real issue,” Nuland said.

In November 2013 the Washington Post went even further, falsely reporting that Assange was "not under sealed indictment" based on comments from anonymous US officials.

“We will treat this news with skepticism,” said WikiLeaks spokesman Kristinn Hrafnsson. “Unfortunately, the U.S. government has a track record of being deceptive.”

*

Also on 26 January 2011, the New York Times' executive editor Bill Keller published a ridiculously long article about his dealings with WikiLeaks during the previous year. The article was one of several New York Times essays that were compiled into a rushed-out book to help the cash-strapped newspaper (propped up by a $250 million loan from Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim, with print revenue down 26%) boost profits from massive public interest.

Keller was intent on establishing his own narrative of events, thus insulating his newspaper from allegations of irresponsible reporting. He dismissed Assange as "thin-skinned… arrogant… elusive, manipulative and volatile (and ultimately openly hostile to The Times and The Guardian)." But he also provided qualified support for WikiLeaks in the face of US government threats:

But while I do not regard Assange as a partner, and I would hesitate to describe what WikiLeaks does as journalism, it is chilling to contemplate the possible government prosecution of WikiLeaks for making secrets public, let alone the passage of new laws to punish the dissemination of classified information, as some have advocated. Taking legal recourse against a government official who violates his trust by divulging secrets he is sworn to protect is one thing. But criminalizing the publication of such secrets by someone who has no official obligation seems to me to run up against the First Amendment and the best traditions of this country.

Five days later, 60 Minutes aired a lengthy interview with Assange where he claimed "our founding values are those of the U.S. revolution".

60 Mins: Someone in the Australian government said that, “Look, if you play outside the rules you can’t expect to be protected by the rules.” And you played outside the rules. You’ve played outside the United States’ rules.

Assange: No. We’ve actually played inside the rules. We didn’t go out to get the material. We operated just like any U.S. publisher operates. We didn’t play outside the rules. We played inside the rules.

60 Mins: There’s a special set of rules in the United States for disclosing classified information. There is longstanding -

Assange: There’s a special set of rules for soldiers. For members of the State Department, who are disclosing classified information. There’s not a special set of rules for publishers to disclose classified information. There is the First Amendment. It covers the case. And there’s been no precedent that I’m aware of in the past 50 years of prosecuting a publisher for espionage. It is just not done. Those are the rules. You do not do it.

Assange insisted that WikiLeaks’s 2010 releases would in fact be "encouragement to every other publisher to publish fearlessly."

If we’re talking about creating threats to small publishers to stop them publishing, the U.S. has lost its way. It has abrogated its founding traditions. It has thrown the First Amendment in the bin. Because publishers must be free to publish.

*

Arab Spring

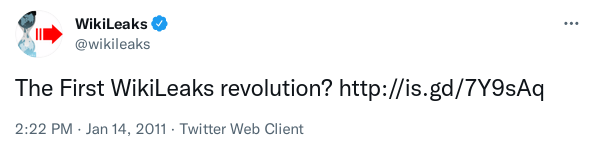

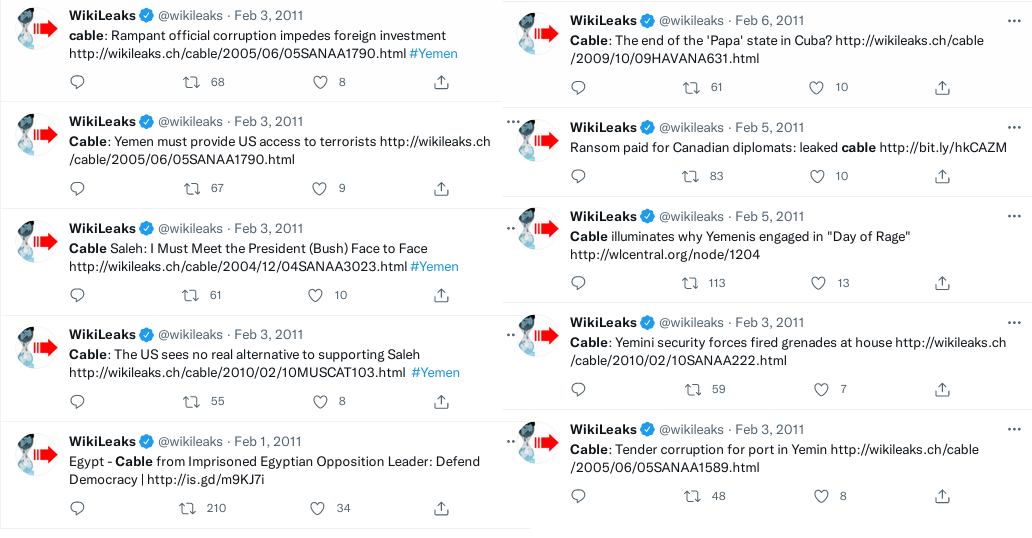

Meanwhile, the world was in turmoil. Tunisia’s president Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali fled his country in mid-January 2011 - despite winning 89% of the vote two years earlier - and became the first dictator to fall in a series of popular uprisings now called the Arab Spring. The widespread protests were at least partly triggered by WikiLeaks' Cablegate publications, which provided hard proof of endemic corruption across the Middle East.

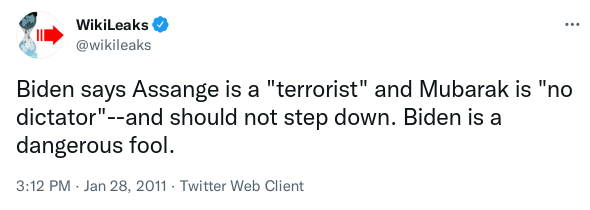

The final days of January saw huge protests in Egypt, with US-backed dictator Hosni Mubarak repeatedly shutting down the Internet to stem the flow of information. On 28 January WikiLeaks released a first batch of new Egyptian cables. On 29 January activists began faxing the WikiLeaks cables into Egypt to bypass the Internet blockade. Mubarak resigned less than two weeks later.

Critics accused Assange of trying to take full credit for these revolutions, although he did no such thing. On 30 January 2011 WikiLeaks tweeted that Al Jazeera’s new satellite TV network was also a critical factor:

Yes, we may have helped Tunisia, Egypt. But let us not forget the elephant in the room: Al Jazeera + sat dishes

The Arab Spring saw many online activists joining the #Anonymous global collective to bring down government websites in the Middle East with massive Denial of Service (DDos) attacks. Western analysts could hardly complain when such activists helped bring down authoritarian government sites overseas, but it was a different story for those who had targetted US and British websites in the previous year.

On 28 January the FBI announced that it had executed over forty search warrants in response to DDoS attacks, while five people were arrested in the United Kingdom.

Anons reacted to these arrests by publishing an open letter to the UK government, ridiculing the harsh penalties - a maximum 10 years imprisonment and fines up to £5000 - for a crime that temporarily brought down websites but left no permament damage.

The fact that thousands of people from all over the world felt the need to participate in these attacks on organisations targeting Wikileaks and treating it as a public threat, rather than a common good, should be something that sets you thinking. You can easily arrest individuals, but you cannot arrest an ideology.

*

The Guardian’s "War On Secrecy" Book

By the start of February 2011, barely two thousand of the 250,000 leaked cables had been published. But like the New York Times (above) Guardian journalists David Leigh and Luke Harding were already rushing out a book: "Wikileaks: Inside Julian Assange’s War on Secrecy". An excerpt from the Preface by their boss Alan Rusbridger was published three days before the book’s release, mostly complaining about the difficulties of working with WikiLeaks' unconventional founder. The Guardian EIC approvingly quoted Slate columnist Jack Shafer:

"Assange bedevils the journalists who work with him because he refuses to conform to any of the roles they expect him to play."

Rusbridger said it was "an interesting matter for speculation" whether US media atttitudes would change if Assange was ever to be prosecuted. But it would be difficult to do that "without also putting five editors in the dock" and that would be "the media case of the century".

"It was astonishing to sit in London reading of reasonably mainstream American figures calling for the assassination of Assange for what he had unleashed. It was surprising to see the widespread reluctance among American journalists to support the general ideal and work of WikiLeaks. For some it simply boiled down to a reluctance to admit that Assange was a journalist."

Nevertheless, and even though the Guardian was still publishing dozens of stories about the cables every week, Rusbridger made it clear that he had no further use for Assange:

"While Assange was certainly our main source for the documents, he was in no sense a conventional source – he was not the original source and certainly not a confidential one. Latterly, he was not even the only source… When, to Assange’s fury, WikiLeaks itself sprang a leak, the irony of the situation was almost comic."

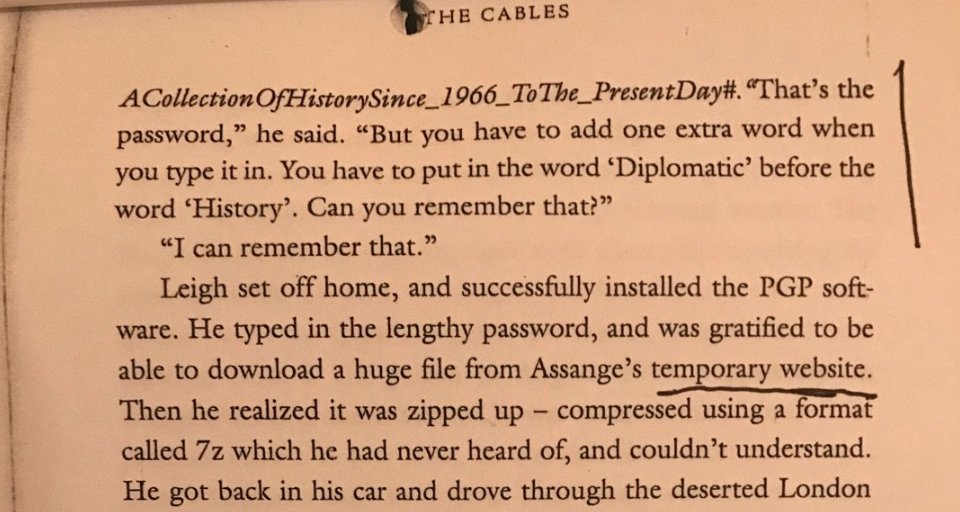

Rusbridger might not have thought it was so funny if he knew that his brother-in-law’s book was also about to cause a far worse leak, with profound repercussions. One of the chapter headings in the book contained the passphrase to unlock the entire Cablegate archive. This was not a conventional password. Assange had personally written it down for Leigh, but even then he took an extra precaution (in cryptographic terms, an additional "salt"):

Assange wrote down on a scrap of paper:

ACollectionOfHistorySince_1966_ToThe_PresentDay#

"That’s the password," he said. "But you have to add one extra word when you type it in. You have to put in the word 'Diplomatic' before the word 'History'. Can you remember that?"

As the book repeatedly shows, Assange was far from impressed by Leigh’s technological expertise. Leigh could not even open a standard compressed file, and needed help to view the files even after the passphrase had unlocked them.

Leigh later complained that Assange told him the passphrase was only temporary. Assange vehemently denied this. It was in fact the secure server, which Leigh used to access the archive, that was temporary. A Guardian statement later made this clear:

"The embassy cables were shared with the Guardian through a secure server for a period of hours, after which the server was taken offline and all files removed, as was previously agreed by both parties."

Leigh himself even noted this in his book, as Kristinn Hrafnsson pointed out:

For years to come, however, Guardian journalists would accuse Assange of sloppy security while insisting their colleagues did nothing wrong. Tellingly, Leigh and Harding only published the lengthy passphrase in their book because it was an illuminating example of the extreme lengths Assange took to guarantee security.

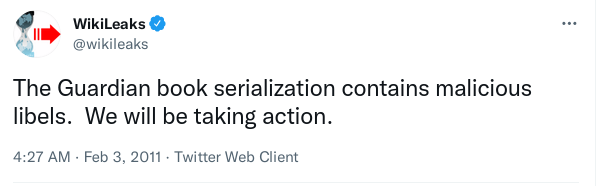

For the time being, at any rate, nobody was going public with concerns about the Cablegate passphrase being published, because the compressed archive files remained secret. But there were plenty of other problems with the new Guardian book.

One of the book’s most explosive claims regarded a July 2010 dinner at London’s Moro restaurant, where journalists working on the Afghan War Diaries had gathered to discuss redactions. According to David Leigh, when discussion turned to protecting the names of the US military’s Afghan informants, Julian Assange said: “They’re informants, they deserve to die.” Assange vigorously denied ever saying this, but the alleged quote was repeated for years to come as proof of his alleged "disregard for human lives".

That dinner was attended by Guardian journalists David Leigh and Declan Walsh, who supported Leigh’s claim. But John Goetz, who also attended the dinner with his Der Spiegel colleague Marcel Rosenbach, insisted that Julian Assange had never said such a thing. Rosenbach could not remember Assange saying it, but could not be certain he never said it. The only other person at that dinner was Assange himself, who declared:

This is just nonsense: I said some people held that view, but that we would edit the documents to preserve their essential content and not throw harm in people’s way if we could avoid it… In actual fact, we had been burning the midnight oil on redactions from early on.

Who to believe? A clue comes from Australian journalist Mark Davis, who attended many of the Afghan War Diaries meetings as a privileged insider filming the documentary “Inside WikiLeaks”. Davis later ridiculed Guardian claims that Assange had a "cavalier attitude" to innocent lives.

"If there was any cavalier attitude, it was the Guardian journalists. They had disdain for the impact of this material.”

Davis said the Guardian journalists frequently engaged in "gallows humour" which Assange avoided. And the Guardian wanted to rush publication before redactions were finished, forcing Julian to work all night doing the job himself.

“Julian wanted to take the names out,” Davis said. “He asked for the releases to be delayed.” The request was rejected by the Guardian, “so Julian was left with the task of cleansing the documents. Julian removed 10,000 names by himself, not the Guardian.”

Davis said the Guardian journalists did not care about redactions because they expected WikiLeaks to be blamed, not them or their media partners. He recalled a conversation between Nick Davies and David Leigh, when Assange was not present:

“It occurred to Nick Davies as they pulled up an article they were going to put in the newspaper — he said ‘Well, we can’t name this guy'. And then someone said ‘Well he’s going to be named on the website.’ Davies said something to the effect of ‘We’ll really cop it then, if and when we are blamed for putting that name up.’ And the words I remember very precisely from David Leigh was - he gazed across the room at Davies and said: ‘But we’re not publishing it.’”

Mark Davis accused the Guardian and the New York Times of attempted “subterfuge… pushing Julian out to walk the plank”. If WikiLeaks published the cables first, before media partners ran their stories, Assange would be legally to blame for any repurcussions. But their plan failed due to technical issues: when the first Afghan War Log stories were published, WikiLeaks was offline. Neverthess, media partners' stories falsely stated that WikiLeaks had "published" the files, not them.

“WikiLeaks did not publish for two days,” Davis said. The Guardian and the Times had “reported a lie. They set Julian up from the start.”

Davis' testimony was reinforced by another Australian journalist, Iain Overton, who worked with Assange on the Iraq War Logs months later.

In a July 2011 article, Alan Rusbridger, who was on a salary package around £400,000 at the time, casually remarked:

"Everyone knows how WikiLeaks ended…"

This was another common smear: WikiLeaks had lost staff, their submission system was broken, and they would never publish any major leaks again. But WikiLeaks was not quite dead yet.

Anti-Semitism Smears

The next major bombshell from the Guardian’s new book was that Julian Assange was an anti-Semite, or at least worked closely with an allegedly "notorious anti-Semite" named Israel Shamir, who just happened to have been born Jewish, lost family members in the Nazi Holocaust, and trained with the Israeli Defence Force. This was the first of many bizarre anti-Assange allegations from new Guardian journalist James Ball, who had covered the Iraq War Logs stories for the Bureau of Investigative Journalism before very briefly joining WikiLeaks in November 2010.

Although Ball joined the Guardian in February 2011, the 31 January 2011 Guardian article promoting the Guardian book refers to him only as an anonymous "insider" who claimed that Israel Shamir had "demanded copies of cables about 'the Jews'".

James Ball re-hashed this claim under his own name in a November 2011 Guardian article where he stated:

Shamir aroused the suspicion of several WikiLeaks staffers – myself included – when he asked for access to all cable material concerning "the Jews", a request which was refused.

Shamir responded that it was Ball himself who had given him these cables.

You did it even twice: just before my departure you came to me on your own initiative and kindly handed me "a better file on Jews", twice as big as the previous one.

James Ball, who had also previously worked as a researcher for Heather Brooke (via whom the Guardian supplied the Cablegate archive to the New York Times), further stated:

Shamir has a years-long friendship with Assange, and was privy to the contents of tens of thousands of US diplomatic cables months before WikiLeaks made public the full cache.

Shamir’s "years-long friendship with Assange" turned out to be at best a wild exaggeration. And if Shamir really had such access to the files, why would he have needed to ask anyone for them?

These "anti-Semite" claims, smearing Julian Assange and WikiLeaks by association with Shamir, were repeated and repeated again by Britain’s Private Eye magazine, with a tired Julian Assange denying that he made anti-Semitic remarks about a "Jewish conspiracy" in frustrated phone calls with editor Ian Hislop.

Jennifer Lipman from the Jewish Chronicle, who "worked with Julian Assange in the past" and "never heard him express any antisemitic sentiments", wanted an explanation. She noted that that Julian Assange had also been called "an agent of Mossad because the WikiLeaks cables did not provide enough evidence of Israeli government wrongdoing". Even the non-profit Index on Censorship, which had awarded Assange their new media prize in 2008, weighed in with questions.

WikiLeaks was eventually forced to issue a lengthy response which said in part:

Israel Shamir has never worked or volunteered for WikiLeaks, in any manner, whatsoever. He has never written for WikiLeaks or any associated organization, under any name and we have no plan that he do so. He is not an 'agent' of WikiLeaks. He has never been an employee of WikiLeaks and has never received monies from WikiLeaks or given monies to WikiLeaks or any related organization or individual. However, he has worked for the BBC, Haaretz, and many other reputable organizations.

It is false that Shamir is 'an Assange intimate'. He interviewed Assange (on behalf of Russian media), as have many journalists. He took a photo at that time and has only met with WikiLeaks staff (including Asssange) twice. It is false that 'he was trusted with selecting the 250,000 US State Department cables for the Russian media' or that he has had access to such at any time.

- Note

-

Shamir’s son Johannes Wahlström also published Cablegate stories in Sweden. Complaints about WikiLeaks' connection to Shamir were first raised in Swedish media after he published a September 2010 article suggesting the sex allegations against Assange could be a CIA "honeypot". These issues were first addressed by the Guardian in 17 December 2010 blog that falsely called Shamir "WikiLeaks’s spokesperson and conduit in Russia". James Ball thought it was very odd that Shamir was introducted to WikiLeaks staff as "Adam" but he was widely reported to have used at least six names and the contact email address at the bottom of his September 2010 story was "adam@israelshamir.net".

WikiLeaks also noted that Shamir had been obliged, like all media partners, to sign a non-disclosure agreement before getting access to any files. And yet James Ball two months later criticised Assange for forcing staff to sign non-disclosure documents. Ball claimed that he "inadvertently" leaked a copy of his own non-disclosure agreement, which he had refused to sign, calling it "by orders of magnitude the most restrictive I have ever encountered". As usual with media critics, Assange was damned if he did and damned if he didn’t. Without a hint of self-awareness, James Ball concluded that WikiLeaks, the world’s leading transparency organisation, "needs to get out of the gagging game."

James Ball further reported that Israel Shamir had given unredacted US cables to the President of Belarus, Alexander Lukashenko, who then used that information to crack down on dissenters. Again there was no proof for this allegation, just a photo of Shamir outside the steps of the Belarus Presidential Administation Building in Minsk on the day elections were being held, 19 December 2010. Shamir wrote an article explaining why he was in his mother’s home town of Minsk at the time, but nevertheless Julian Assange was falsely accused for years to come of endangering the lives of Belarussian dissidents.

It seems the new cables on Belarus were actually first published by "Russian Reporter", a magazine that was condemned by the Russia’s state-owned Moscow Times, who also called Shamir a "notorious anti-Semite". Human rights group Charter 97 then published articles about the cables, criticizing the Lukashenko regime. Belarus police brought down their website, raided their offices, and arrested them. But nobody was harmed as a direct result of the cables being published, as even US government officials later admitted.

There were massive protests after Lukashenko claimed victory in the elections. Opposition leader Andrei Sannikov was just one of dozens imprisoned. But a year later, Sannikov’s sister Irina, a spokesperson for the Free Belarus campaign, invited Julian Assange to host a Q & A session at the premiere screening of their film, "Europe’s Last Dictator". It was then more clear than ever that Assange had been helping Belarussian dissidents in the background, not helping get them killed. Nevertheless Britain’s New Statesman magazine complained that "to dignify Assange with a place on the podium at an event about Belarus is to mock the men and women who endure the brutality of Lukashenko". Obviously the author, a "freelancer from India" whose work had appeared in the Boston Globe, the Chicago Tribune, and the Los Angeles Times, knew more about Belarussia than the dissidents who had invited Assange to speak.

It’s worth noting that the USA meddles a great deal in former Soviet bloc nations nations like Belarus. According to the New Statesman, Shamir expressed delight when US-backed agents were exposed. But as WikiLeaks cautioned:

We do not have editorial control over the hundreds of journalists and publications based on our materials and it would be wrong for us to seek to do so. We do not approve or endorse the writings of the world’s media. We disagree with many of the approaches taken in analyzing our material.

Of course, the great benefit of WikiLeaks releases is that readers can view the source material for themselves and draw their own conclusions. It is also worth noting that UK public support would be critical to Julian Assange in the years ahead, and the people most likely to support WikiLeaks in 2011 were anti-war, anti-Establishment, left wing types. But the UK’s most "left wing" UK publications - the Guardian, New Statesman and Private Eye - were all quickly lining up to criticize the WikiLeaks founder. Right wing media organisations like the Telegraph or the Times gave Assange and WikiLeaks far less column space (almost all negative). By design or accident, the local audience most likely to support Assange was being actively discouraged from doing so.

*

While this confected "anti-Semitism" debate raged, Stephen Spielberg’s DreamWorks studio had quietly bought the rights to both the Guardian’s "WikiLeaks: Inside Julian Assange’s War on Secrecy" and Domscheit-Berg’s poor-selling book (now with an English version, still low sales). The untrustworthy movie that eventually resulted would predictably become a miserable flop ("the worst opening of the year so far for a movie opening in more than 1,500 theaters"). But Alan Rusbridger was gushing with excitement:

"It’s Woodward and Bernstein meets Stieg Larsson meets Jason Bourne. Plus the odd moment of sheer farce and, in Julian Assange, a compelling character who goes beyond what any Hollywood scriptwriter would dare to invent."

And David Leigh, who had recklessly published the Cablegate passphrase, was recklessly throwing around accusations of recklessness. He said Assange was a "reckless amateur" journalist who was "being reckless and opportunistic" by "palling up with" Russia and "giving material to very unsuitable people. He complained that WikiLeaks staff "like to see themselves as having some God-like virtue which enables them to behave in some pretty reckless and unethical ways."

Leigh’s co-author Luke Harding, who won Private Eye’s 2007 Plagiarist of the Year award, was denied entry back into Moscow after publishing numerous stories about US cables critical of Russia. But years later Assange was being widely slandered as "a Putin puppet" with Luke Harding publishing incriminating lies about Assange in the Guardian and seemingly fabricating key conspiracy theories.

Former Guardian journalist Jonathan Cook explained that Leigh and Harding’s "well-known animosity" towards Assange was "at least partly due to Assange refusing to let them write his official biography, a likely big moneymaker".

The hostility had intensified and grown mutual when Assange discovered that behind his back they were writing an unauthorised biography while working alongside him.

- NOTE

-

To their credit, Nick Davies and Alan Rusbridger later opposed the USA’s attempts to extradite Assange from Britain, although Rusbridger admitted he wasn’t following the case closely. James Ball also opposed extradition while continuing his pathetic attacks on Assange. David Leigh, who vigorously supported extradition to Sweden, also opposed US extradition. Luke Harding, whose money-making book became central to the US extradition case, said nothing.

*

The Fall of Gadddafi

After toppling leaders in Tunisia and Egypt, the Arab Spring protests spread into Algeria, Jordan, Yemen, Bahrain, Syria, Kuwait, Morrocco, Oman, Sudan and even Saudi Arabia. By March 2011 the world’s focus was on oil-rich Libya, where eccentric leader Colonel Muammar Gaddafi had been in power since 1969. In February alone WikiLeaks posted some 17 tweets mentioning Libya and released hundreds of US diplomatic cables about the North African nation.

One of the leaked cables revealed that Gaddafi, who claimed to be a pious Muslim, "relies heavily" on a "voluptuous blonde" Ukranian nurse, who later sought asylum in Norway.

Gaddafi claimed that Libyan protesters were "drugged" and/or linked to al-Qaeda, swearing that he would die a martyr rather than leave Libya. After the Libyan army opened fire on protesters in the rebellious city of Benghazi, many senior officials resigned or joined rebel groups, prompting a six months-long civil war.

NATO forces imposed a no-fly zone over the country in March, following a UN Resolution in February. US President Obama claimed the USA was only reluctantly getting involved:

"Mindful of the risks and costs of military action, we are naturally reluctant to use force to solve the world’s many challenges. But when our interests and values are at stake, we have a responsibility to act.”

Leaked emails from Hillary Clinton, published by WikiLeaks in 2016, later showed the US Secretary of State was the principal architect of the US-lead invasion. Assange branded her "the butcher of Libya" and claimed she used the invasion as a basis for her failed 2016 Presidential campaign. Over 1,700 of Clinton’s leaked emails mentioned Libya.

Assange critic Tom Watson instead blamed WikiLeaks for the invasion, describing it as the first WikiLeaks War:

The smartest pro-transparency analysts have always realized that the revelations the U.S. cables represented would almost certainly lead to unforeseen consequences, if not armed conflict.

Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi was finally overthrown on 23 August 2011. He was killed on 20 October 2011 by rebels who found him hiding in a tunnel in his hometown of Sirte. When Hillary Clinton was told of Gaddafi’s brutally violent death she happily quipped:

"We came, we saw, he died."

*

*

The author of this book can be found on Twitter: @Jaraparilla

*

Home - Genesis - 2007 - 2008 - 2009 - Early 2010 - Mid 2010 - Late 2010 - End 2010 - Early 2011 - Mid 2011 - Late 2011 - End 2011 - Early 2012 - Late 2012 - Early 2013- Late 2013 - 2014 - 2015 - Early 2016 - Late 2016 - 2017-19

Copyright Gary Lord 2021, 2022, 2023